Italian Banking, Texas Style

In a world of floating bubbles, there are innumerable pins. Mr. Dodd and Mr. Frank has the masses sleeping soundly with their encyclopedia of financial regulations keeping bankers from extending dodgy loans and borrowers RSVPing their monthly statements. The financial world is sound with a slumbering VIX and the markets FANGtastic.

However, Bloomberg reports, “Italian finance officials and the European Commission are racing to find a solution for two troubled banks in the northern Veneto region that have weighed on the nation’s financial system.”

“La Stampa, quoting officials in the EU and the Treasury in Rome, said the current rescue plan has been determined to be unfeasible,” writes Kevin Costelloe and Sonia Sirletti.

Spoiled sports looking for disaster would be met with the following as Exhibit A: Spain’s Banco Popular had the dubious honor of being the first financial institution to be resolved under the EU’s Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive, with shareholders and subordinated bondholders were “bailed in” before the bank was sold to Santander for a single euro. “At first the operation was proclaimed a roaring success,” reports Don Quijones for Wolf Street.

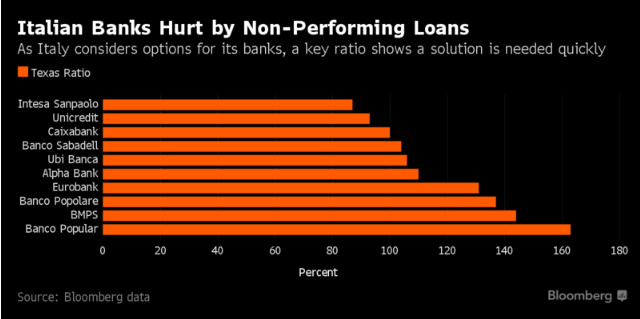

Italy has a banking system reminding some of Texas. The Texas-Ratio that is. Michael W.D. Kurz, writing for The Market Mogul,

Already one year ago, in June 2016, non-performing loans were piling up at Italian banks, €360bn to be precise. That was a third of all such loans in the Euro-Area. And the situation hasn’t changed much since then. New research suggests that, as of March 2017, 114 out of almost 500 banks in Italy are in trouble. These banks all have so-called Texas-Ratios (TR) of 100% or more.

The Dallas Fed’s Thomas Siems explained Texas-Ratio in 2012,

To calculate the Texas ratio, the book value of all nonperforming assets (including other real estate owned) is divided by equity capital plus loan-loss reserves. Only tangible equity capital should be counted in the denominator—the intangible parts, like goodwill, are excluded. In the simplest terms, the Texas ratio measures a bank’s likelihood of failure by comparing its bad assets to available capital. When this ratio exceeds 100 percent, a bank’s capital cushion is no longer adequate to absorb potential losses from troubled assets. In other words, the bank is at greater risk of going bust.

Siems tells the story that in 1988, 20 percent of Texas banks had 100 percent or more Texas-ratios and the next year the state had 133 failures. In fact, “Texas led the nation in bank failures every year from 1986 through 1992.” So the name stuck.

Chief economist Siems uses the ratio to identify where bank failures would be clustered after the 2008 financial crash. Sure enough, Georgia and Florida led the way.

Back in the old world Monte Dei Paschi di Siena – the oldest bank in the world – and two Venetian banks, Popolare di Vicenza and Veneto Banca, have Texas-Ratios of 269% (Monte Dei Paschi), 210% (Popolare di Vicenza) and 239% (Veneto Banca), reports Mr. Kurz. Meanwhile Italy’s two largest banks may also be dead banks walking. Unicredit and Intesa Sanpaolo both have Texas-Ratios above 90%.

Kurz writes, “But by resolving the most troubled banks – always one at a time from the most important or urgent cases to the least important ones – could yield a chance to restore market forces and the Spanish example shows that it is possible without causing havoc to the markets.”

However, crashes don’t give regulators a chance to solve these problems one at a time in an orderly way.