Meet the New Nonprime, Same as the Old Subprime

It’s back. Renamed and repackaged, and fully compliant with Messrs. Dodd and Frank. "Making credit available to borrowers who are subprime is national policy and it is an important part of economic growth," says Julian Hebron, head of sales at RPM Mortgage in Alamo, California. "It's untrue to call it a scourge."

Across the pond, “Everyone in the financial services industry is terrified of using the term ‘sub-prime’ – so you will notice that a new lexicon has developed to describe the market, with ‘impaired credit’, ‘credit repair’ and ‘complex prime’ among the labels commonly used” writes Patrick Collinson and Rupert Jones for The Guardian.

Don’t call it scourge or subprime, for that matter. It’s nonprime. Dan Perl told CNBC, subprime “sounds kind of Neanderthal, doesn't it? It sounds almost like you're a monkey and humans are better. But nonprime has a nice ring to it."

A veteran lender to the less than creditworthy, Mr. Perl walked away in 2007 and sat out last decade’s crash. Now he’s back at age 68. Ben McLannahan writes that the nonprime sector, “is on course to produce about $10bn this year — a tiny slice of America's $1.6tn overall home-loan market but one that's growing rapidly.”

“The way Perl and his peers see it, there's nothing shady or menacing about the business of subprime. On the contrary, they say, specialist lenders in this area are performing a vital service for the world's largest economy,” McLannahan explains.

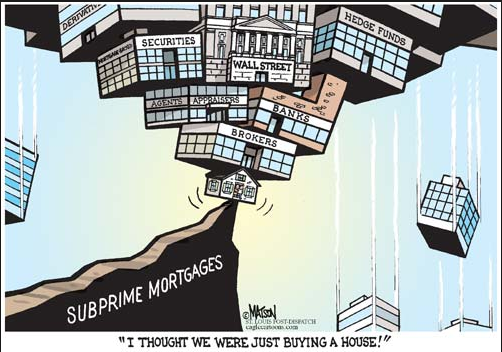

The worry is mortgage lending will slid right back to the early 2000’s when anyone could get a mortgage, or two, or three. Down payment, job, good credit history, not required. After all, Wall Street has rediscovered its appetite for higher yielding junky paper. “The market for securitising subprime loans is picking up, too, spreading the risk of default in much the same way as before,” writes McLannahan. “Fitch, the credit rating agency, expects $3bn of issuance of nonprime mortgage-backed securities (MBS) this year, up from about $1bn over the previous 18 months. (Back in January, it was predicting $2bn for the year.)”

This is reminiscent of the bad old days. "Everyone was complicit," says Mike Fierman. "You felt trapped; investors were demanding more loans than could be produced in a responsible way. The only way to produce that kind of volume was to be irresponsible."

To feed the machine, lenders were going after "gardeners and serving maids and house cleaners and gas-station attendants and strippers on poles," says Perl.

This time there are no negative amortization and liar loans. A borrower’s ability to pay must be verified. However, packaging enough squeaky clean paper to fill Wall Street’s appetite is difficult. For instance, “In a $250m MBS deal in June, more than 40 per cent of borrowers who got mortgages bought by Deephaven had had a prior "credit event" such as a bankruptcy, foreclosure or short sale, according to Kroll, a credit rating agency. The deal was roughly six times oversubscribed, nonetheless,” writes McLannahan.

Wall Street giants Pimco and Blackstone are creeping back in and it’s just a matter of time before the banks ramp up their nonprime numbers. The ratings agencies have returned (other than Moody's) giving the MBS products their stamp approval. Bill Ashmore, who runs California mortgage company, Impac, thinks the market will grow to $100 billion.

As they were in in the last housing meltdown, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac are the catalysts. William Poole wrote on CNN in March of this year,

Today, the Fed is again ignoring the GSEs and their potential contribution to future instability. According to Freddie's 2016 annual report, "Expanding access to affordable mortgage credit will continue to be a top priority in 2017." Fannie/Freddie have redefined "subprime" to a credit rating of below 620; previously, these firms and banking regulators had used 660 as the dividing line that defined a subprime borrower. Now by using the lower number, they may be buying even weaker mortgages than before the financial crisis.

Freddie says 36% of its obligations are "credit enhanced," typically used for weaker mortgages. However, as Poole points out, “The insurance against default is only as good as the enhancing firms, and none is rated above BBB+. If these weak subprime mortgages begin to fail in large numbers, so also will the insuring companies.”

Poole believes, the market is riskier than 2008 because back then “there was some market discipline, however imperfect it was, because potential buyers of mortgages would look at their quality carefully.” Today, “only Fannie and Freddie are examining the quality of the mortgages,” he writes “And it is taxpayers who would carry the burden of bailing out Fannie and Freddie, since their obligations are guaranteed by the US government.”

As Jim Grant often says, knowledge in the sciences is cumulative, in finance, it’s cyclical.