Debt Conceit

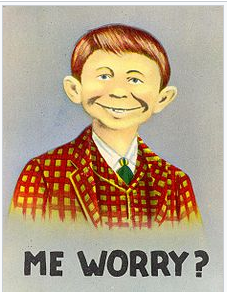

Jerome Powell raised the Fed funds rate another 25 basis points (from 1,75% to 2%), promised two more increases, and markets collectively yawned. The 10-year bond trades below three pecent and the DJIA stands defiantly above 25,000. It’s a mad, mad, madworld with Alfred E. Newman saying, “What? Me worry?”

The markets believe Mr. Powell is cooking his porridge just right--not too hot, not too cold--and, most importantly, not blow up the stove, or the whole house. “The decision you see today is another sign that the U.S. economy is in great shape,” Mr. Powell said in plain English. “Most people who want to find jobs are finding them.”

But, as rates normalize, the clock will tick on a record amount of debt. Steven Pearlstein writes that lenders,

are adding a short-term sugar high to an already booming economy. And once again, they are diverting capital from productive long-term investment to further inflate a financial bubble — this one in corporate stocks and bonds — that, when it bursts, will send the economy into another recession.

Ten years of world-wide ZIRP and QE has sent stocks, bonds, art and cryptos skyward. The stocks of companies that will never make a profit, Tesla for instance, trade for over $300 a share.

Some have called this the “everything bubble.” Jim Chanos calls it the “fraud cycle.” Chanos told Lynn Parramore, “The longer the cycle goes on, the easier it becomes for the dishonest and the fraudsters to ply their trade because people will begin to believe in things that they shouldn’t financially.”

The famed short-seller claims, “Cryptocurrency is a security speculation game masquerading as a technological breakthrough.”

Pearlstein ominously writes,

Welcome to the Buyback Economy. Today’s economic boom is driven not by any great burst of innovation or growth in productivity. Rather, it is driven by another round of financial engineering that converts equity into debt. It sacrifices future growth for present consumption.

Corporate America is borrowing like mad to buy back stock. Pearlstein tells us the staggering numbers. “A decade ago, in 2008, there was $2.8 trillion in outstanding bonds from U.S. corporations. Today, it’s $5.3 trillion, after the record $1.7 trillion of new bonds issued last year, according to Dealogic, and $500 billion more issued this year.”

Investors have spent a decade of reaching for yield and billions in junk paper have been sucked up by ETFs to satisfy investor appetite. “A decade ago, about $15 billion worth of bond ETFs were being traded,” Pearlstein writes. “Today, that market has grown to $300 billion.” That would be 20 times more in junky stuff.

Companies are also borrowing from banks, that are in turn bundling those loans into CLOs (collateralized loan obligations), similar to how home mortgages were layered together a decade ago.

Mariarosa Verde, senior credit officer at ratings agency Moody’s, warned last month, “the record number of highly-leveraged companies has set the stage for a particularly large wave of defaults when the next period of broad economic stress eventually arrives.”

A junk default wave will send ETF and CLO investors into a panic, crushing prices and creating a 2008-style liquidity event.

“But because these products are relatively new, nobody really knows how they will perform in a crisis,” Pearlstein writes and refers to the CDS market in 2008. “There is also the danger of contagion — that panic selling and falling prices of corporate bonds and ETFs will spread to other credit markets.”

The federal government is on a borrowing binge with debt service continuing to rise with rates and the amount owed. Student loan debt and subprime auto loans owed also continue to rise to record levels.

“Banks will reap what they have sowed in having created all this debt,” said James Millstein, an expert in corporate and government debt who oversaw the restructuring of insurance giant AIG for the treasury during the 2008 financial crisis. “Banks are still the most highly leveraged financial institutions in the economy. They remain vulnerable to a recession-driven increase in delinquencies and defaults in their corporate, real estate and household loan books.”

But for now, “don’t worry, be happy” is what the markets are telling us because as Thorsten Polleit wrote last year on mises.org, “central banks have put investor risk aversion to sleep: Under their guidance, financial markets are now betting on, and have high confidence in, monetary policy makers successfully fending off any new problems in the economic and financial system.”

Collectively, investors never remember central bankers' fatal conceit. They will be reminded again, sooner than later.