Tiny CAP rates, Massive Malinvestment

Jim Grant and Evan Lorenz interviewed Andy McCulloch, head of real estate analytics at Green Street Advisors, recently, talking cap (“capitalization”) rates and real estate values. McCulloch says the owners of high quality real estate have no problem attracting lenders at low rates.

The Unibail-Rodamco deal to buy Westfield for $24.7B including debt, creating the largest owner of shopping centers in the world was discussed given transaction’s sub-4 percent cap rate, again for what some people believe is dead real estate walking--shopping malls.

McCulloch and Green Street believe 300 malls will go away in the next 10 years and a few hundred more will close down in the decade after that.

Since the portfolio includes U.S. and European assets, McCulloch believes the US malls are going for a high 4s cap rate, while the European assets are being sold for a high 3s cap rate.

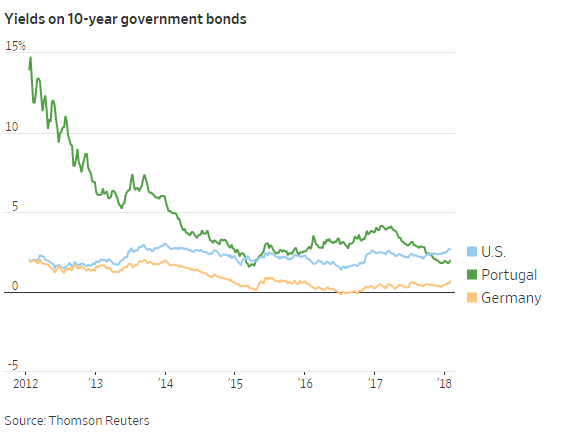

These cap rates would imply that the society time preference in America and Europe are low with people by-and-large saving and delaying gratification. However, Lorenz makes the point that the pint-sized cap rate on European assets is about Mario Draghi’s European Central Bank asset purchases, and Unibail can float sub-2 per cent debt in Europe courtesy of Mr. Draghi and thus can afford to pay the inflated values/tiny cap rates.

This is not the normal course of business. The zero interest rates and negative interest rates seen in Europe serve to misallocate resources and ultimately waste capital.

Murray Rothbard explained,

The fundamental insight of the “Austrian,” or Misesian, theory of the business cycle is that monetary inflation via loans to business causes overinvestment in capital goods, especially in such areas as construction, long-term investments, machine tools, and industrial commodities. On the other hand, there is a relative underinvestment in consumer goods industries. And since stock prices and real-estate prices are titles to capital goods, there tends as well to be an excessive boom in the stock and real-estate markets.

McCulloch makes clear that real estate assets are leveraged assets. Investors borrow to buy real estate. Thus, central bank manipulation of rates effects the real estate industry more than any other. America’s “right-sizing” of the mall industry reflects decades of misallocated real estate capital. Artificial low rates spur real estate prices and demand. “Debt costs definitely impact local values,” says McCulloch.

Grant wonders aloud during the podcast whether these central bank induced low rates are “perpetuating obsolete business models.” For instance the US has 23.5 square feet of retail space per person, compared with 16.4 square feet in Canada and 11.1 square feet in Australia, the next two countries with the most retail space per capita, according to a Morningstar Credit Ratings report.

Last year 51 percent of purchases were made online, allowing consumers to not go anywhere near brick and mortar retail space. The percentage will likely only grow.

It’s not just real estate that low rates energize, mergers and acquisitions also spike when rates are low. Unfortunately, according to the Journal of Property Management, "60 percent to 80 percent of all business combinations undergo a slow, painful demise."

In his book The Synergy Trap, Mark Sirower says valuation models turn on three things: free-cash-flow forecasts, residual value, and a discount rate.

The cost of capital is integral to making these assumptions. The lower the assumed interest rate or cost of capital, the higher the price for the acquisition that the models will justify.

As firms get too big, economic calculation gets muddied because firms do not receive the profit-and-loss signals for their internal transactions. Managers are lost as to how to allocate land and labor to provide maximum profits or to serve customers best.

As these firms grow (especially by acquisition), one part of the company is often the provider and another part of the company is the customer, yet there are no market prices to allocate resources efficiently.

Economic calculation becomes ever more important as the market economy develops and progresses, as the stages and the complexities of type and variety of capital goods increase. Ever more important for the maintenance of an advanced economy, then, is the preservation of markets for all the capital and other producers' goods.

Professor Peter Klein makes the point that

as soon as the firm expands to the point where at least one external market has disappeared, however, the calculation problem exists. The difficulties become worse and worse as more and more external markets disappear, as [quoting Rothbard] "islands of non calculable chaos swell to the proportions of masses and continents. As the area of incalculability increases, the degrees of irrationality, misallocation, loss, impoverishment, etc, become greater."

The world’s central banks have created a world of malinvestment, with the appearance of prosperity, but the illusion will ultimately become a “right-sizing” depression.